Render Unto Caesar

Language Games and the Rise of Post-Rational Politics

This is the second in a series of essays exploring how liberal-rationalist discourse constrains the options for political action in the modern West, and how those constraints can be transcended. Part one is available here.

My last essay argued that adherence to the terms of liberal-rationalist discourse has led conservatism to become severed from its roots in prejudice and affective attachment. (See here1 for a definition of terms.) This used a Burkean conception of prejudice: not the widely-used pejorative sense of crude discrimination, but the unspoken wisdom of lived experience, and intuitive attachment to customs, traditions, ideas, symbols, places, and people. The essay invoked thinkers like Oswald Spengler and Renaud Camus, whose concepts of cultural morphology and ‘replacism’ can help us understand this process of severing as something that is not accidental, but intrinsic to liberal modernity. It implies that the hollowing out of conservatism is a feature of contemporary life, not a bug.

In another essay, I hope to explore why liberal rationalism is not just at odds with conservatism, but fundamentally aberrant: an ideology at war with human nature itself. (You can preview the argument here.2) Here, I plan to use some well-known public figures to explore how liberal-rationalist discourse can be resisted in practice. I’ll then connect this to a wider historical process which we can already see playing out across the West, and which Spengler predicted would herald the final reckoning for Western liberalism and ideological politics in general.

*

Probably the two most powerful people in the world today are Donald Trump and Elon Musk. Both instinctively resist the typical framing of political and media discourse, though in very different ways.

Musk is a highly cerebral engineer, businessman, and public intellectual. While he has historically expressed admiration for liberal values, particularly those related to individual freedom and autonomy, his relationship with liberal rationalism is uneven. Though he aligns with some of its principles, in practice he consistently resists its ideological constraints. Musk often sidesteps the conventional traps of political discourse by questioning assumptions, reframing debates, and using irony or provocation to disrupt expectations. His refusal to operate within prescribed categories often leaves journalists floundering, as in the famous exchange where he explained his commitment to free speech by invoking a scene from The Princess Bride: ‘Offer me money. Offer me power. I don’t care. […] I’ll say what I want to say, and if the consequence of that is losing money, so be it.’

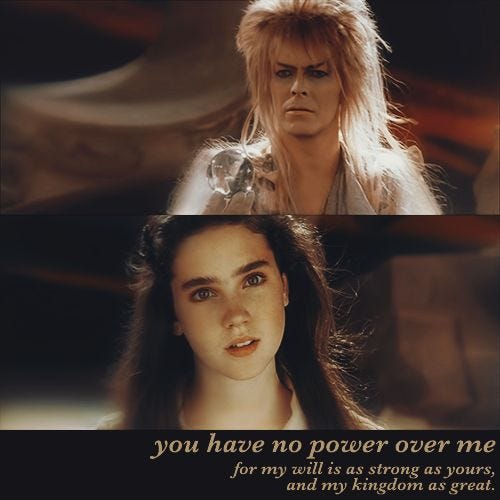

Trump, meanwhile, operates on a more primal, intuitive level, rejecting the rationalist framework by relying on instinct, rhetoric, and dominance games rather than programmatic arguments. He doesn’t try to ‘win’ debates by liberal rules, but changes the rules altogether. This is part of what makes him so infuriating for the media. To continue Musk’s eighties movie theme (and acknowledging the dissonance in comparing Trump to a teenage Jennifer Connelly), this often reminds me of the climactic scene in the film Labyrinth, when the protagonist breaks the magic spell of David Bowie’s Goblin King. The key to breaking his power is simply to deny it: You have no power over me.

Trump and Musk each escape from liberal media discourse by embracing a kind of rhetorical fluidity. This allows them to connect with audiences on an instinctive, pre-rational level. While establishment conservatives have long since been prisoners of the ‘lamestream media’, these figures demonstrate how a different, more visceral mode of engagement can resist its entanglements.

The ability to reject the terms of rationalist debate is not limited to figures on the populist right. A different, but similarly revealing, example comes from Hollywood actor Matthew McConaughey. In recent years, Texas-born McConaughey has tried to position himself as a centrist thought leader who aspires to bring together the warring camps of American life. So far, McConaughey’s efforts in this respect have been only partly successful, and haven’t yet culminated in a run for office. However, it’s still worth noting that McConaughey has largely succeeded in establishing himself as a political figure in the public consciousness, while resisting the media’s attempts to pigeonhole him in partisan terms. Crucially, he’s done so without being discredited or exposed to ridicule.

While some of this can be attributed to sympathetic media handling of a handsome and charming actor, it also speaks to a deeper cultural undercurrent. Unlike Musk and Trump, whose rhetorical styles thrive on disruption and confrontation, McConaughey represents a subtler but no less significant shift: the re-emergence of folk wisdom as an alternative to managerial expertise. His slow-drawling, aphoristic manner evokes a kind of organic, anti-bureaucratic authority that resonates with a public weary of technocratic micromanagement. In this way, his ability to avoid ideological categorization may be less about personal charisma than the public’s instinctive longing for leadership that feels intuitive, experience-based, and independent of elite credentialism. He’s a populist sui generis.

While most rightists will have many political and philosophical reservations about McConaughey, it’s worth observing how he evades the framing traps set by the media. For example, when asked on The View (a major American TV show) whether he could get elected in Texas while being ‘anti-gun’, McConaughey pointedly answered, ‘To give you a direct statement right there, is playing a game I’m not interested in playing.’ Elsewhere, McConaughey has rejected the partisan arrangement of politics, arguing ‘I think we’ve got to redefine politics […] If you’re only there to, by hook or by crook, preserve your party, you’re leaving out 50 percent of the people.’

McConaughey resists being slotted neatly into preordained partisan categories, which is exactly what most conservatives fail to do when they engage on the media’s terms. Instead of accepting the premise of the debate and arguing within it, he typically tries to reframe the conversation entirely or insists on a different mode of engagement. It feels like a form of aesthetic detachment rather than polemical antagonism, and differs from Trump and Musk in that it is less oppositional than digressive. McConaughey projects an aura of authenticity and raw humanity that disarms ideological framing, but unlike Trump, he does not turn the exchange into an overt power game.

Of course, McConaughey has expressed positions on various issues, from gun control to mask mandates. The point is not that one should avoid taking positions at all, but that re-taking discursive control means refusing to play by the rules of liberal rationalism. Moreover, it’s important to distinguish McConaughey’s approach from standard political evasiveness. Unlike the oily careerist who dodges questions to avoid accountability, he strategically resists media framing to avoid the traps baked into its assumptions.

This speaks to a broader point: the power of language games in structuring thought. Conservatives seem not to realize that the moment they start making their case in the language of liberal rationalism, they’re already losing. To better understand this, we can have recourse to Ludwig Wittgenstein, notably his Philosophical Investigations. Wittgenstein challenged the idea that language is fundamentally about abstract, rational propositions describing the world. Instead, he viewed meaning as emerging from language games, in which words gain their significance through use, context, and social practice rather than strict logical definitions.

Liberal rationalists assume that politics is, or should be, conducted within a universal language of reason. This means that political ideas and positions must be justified through abstract argument rather than appeals to (for example) tradition, instinct, or experience. But Wittgenstein’s insight suggests that this is just one way of using language: one particular game among many. It is neither neutral nor absolute, but a historically contingent mode of discourse, shaped by the assumptions of liberal modernity. What presents itself simply as impartial analysis is, therefore, a disguised power claim on behalf of liberal rationalism and its associated moral assumptions.

If we take traditional conservative thought as a counterpoint, we can conceive of its mode of reasoning - what Burke called ‘prejudice’ - as another kind of language game. This is rooted in inherited wisdom, affective attachment, and intuitive distinctions: ours and theirs, good and bad, proper and improper, right and wrong. This kind of language is powerful precisely because it does not rely on rationalist justification, but operates within a shared tradition that does not need to be proven in order to be meaningful. It doesn’t need a ‘why’ because it’s embedded in practice, in life itself, not abstraction. It is not irrational, but pre-rational. And yet, precisely because it resists rationalization, it is systematically excluded from public discourse, dismissed as unthinking, reactionary, or even abusive, rather than recognized as an alternative way of knowing.

What this means, following Wittgenstein, is that conservatives are destined to lose the moment they accept liberal-rationalist premises. By engaging in the wrong kind of language game – by trying to justify their positions through universal reason rather than through tradition, sentiment, and lived experience – they unwittingly concede the field. True resistance would require stepping outside that frame entirely, refusing to engage in the liberal-rationalist game on its own terms, and instead asserting a radically different epistemology. Such a discourse would not be universal, nor should it be. It would belong to us, not them, as its roots are in the primordial truths of heritage and identity.

The return of a more visceral, post-rational politics therefore involves a rebellion against the limits of rationalist language itself. In Wittgensteinian terms, it is the reassertion of a different form of life, which does not seek approval by the standards of liberal discourse but instead claims its own legitimacy on its own grounds.

To take the ultimate example of this, we can consider the attitude of Christ. (See here for an important disclaimer.3) His mode of discourse consistently resisted the rhetorical traps laid by the Pharisees and others who tried to force Him into legalistic or dialectical argumentation. Instead of engaging on their terms, Christ responded with parables, aphorisms, and direct moral imperatives that appealed to intuition, tradition, and lived experience rather than abstract logic. His language was deeply rooted in affective attachment – love, loyalty, sacrifice, belonging – and often deliberately short-circuited attempts to rationalize or systematize it.

This is particularly illustrative when Christ refuses to directly answer questions designed to ensnare, such as when asked whether it’s lawful to pay taxes to Caesar. Rather than giving a legalistic or political argument, He offers a simple, enigmatic statement: Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s (Mark 12:17). This is obviously not an argument in the liberal-rationalist sense, but an assertion of a deeper order of meaning that transcends the narrow frame of the question.

Christ’s entire challenge to the religious and political authorities of the time can be seen as an insistence on a different form of life: one that does not justify itself through the dominant discourse of the age but reorients people towards deeper, more intrinsic truths. This bears directly on Wittgenstein’s critique of rationalist language games. Christ does not try to win the debate within the Pharisaic or Roman framework, but simply refuses to play.

Moreover, Christ did not reason his way to truth through rationalist justification, but embodied it. His speech was not merely rhetorical, but ‘actional’. It reshaped the moral reality of the audience, and compelled them to participate in a new way of living.

Whether in faith or politics, true transformation is never won through argument within a dying system. It comes from stepping outside its logic and speaking in a different register. Now, we must rediscover the source of cultural vitality in the unutterable, undeniable legitimacy of belonging, memory, and inherited wisdom. For now, this kind of discursive resistance is something conservatives can only dream of. But it’s coming.

Even McConaughey, in his own way, shows us the value of refusing to play by the rules of the liberal-rationalist language game. I wonder whether he realizes how subversive this is.

*

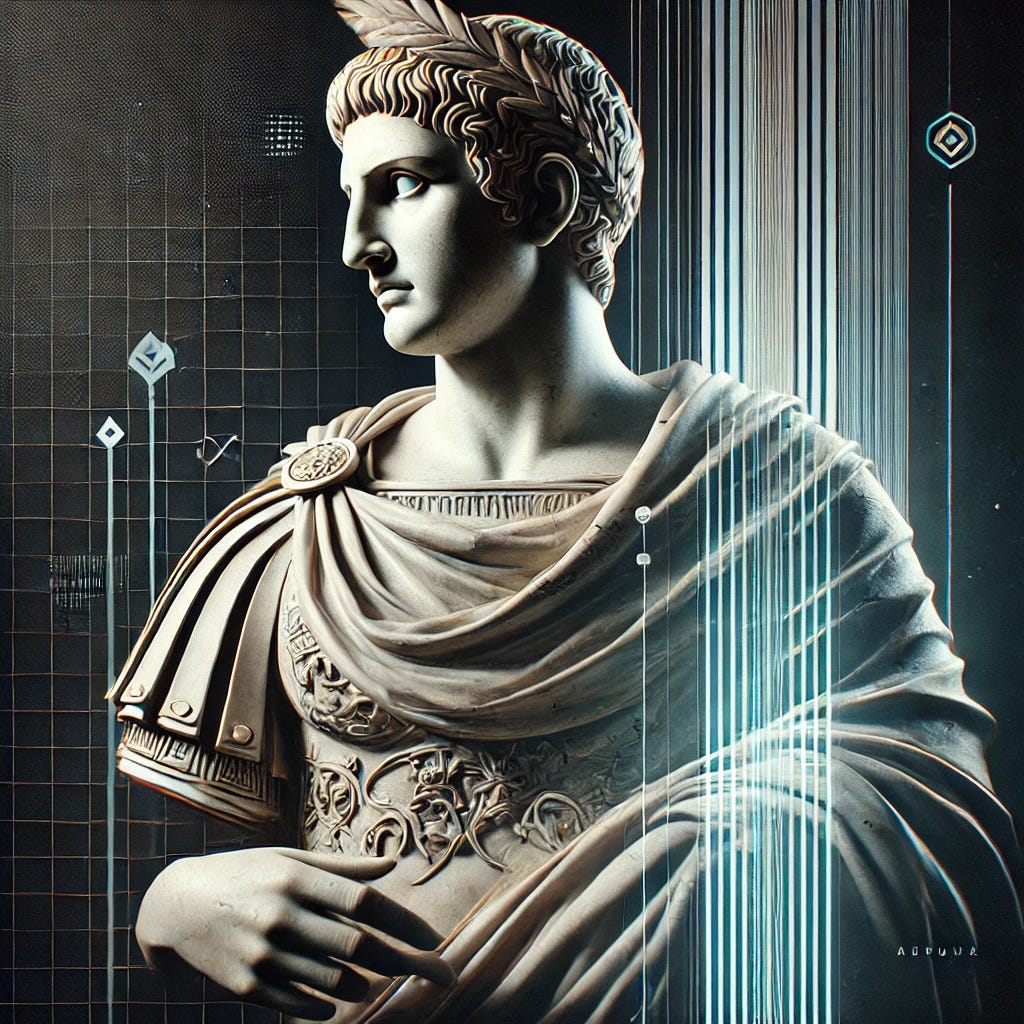

While McConaughey has not yet entered politics, Trump and Musk have transcended the status of charismatic individuals and become, instead, exemplars of a political type: the Caesar. This denotes someone whose power transcends traditional institutions, and instead proceeds directly from their personal wealth, charisma, and influence. Such figures typically come to prominence in times of crisis or perceived dysfunction, as with Napoleon after the French Revolution, when they position themselves as the solution to an ineffective, corrupt, or tyrannical regime. Because they connect directly with the public at large, without relying on intermediary institutions, Caesars tend to be populists. To rally support from the masses, they frame themselves as champions of the common man, standing in opposition to the decadent elites and distant power structures which have lost touch with the needs of the people.

Spengler predicted Caesarism would be the inevitable late stage of Western civilization. This would come about when the structures of parliamentary politics were exhausted, and rationalist ideologies discredited. Then, the moral hegemony of liberal democracy would collapse, and the vacuum would be filled by figures who ruled through force of will and personal authority rather than abstract programmes.

With Trump and Musk – and even, perhaps, one day with McConaughey – we are starting to see the emergence of this type: leaders who can bypass the procedural, rationalist modes of engagement that have broadly defined Western politics for centuries, and instead appeal directly to people’s instincts, loyalties, and grievances. The obvious yearning of Western man for this kind of direct, unfiltered, and authentic leadership points to his deep disillusionment with late-liberal managerialism, and everything it entails.

So, with this in mind, we can look again at how the modern media-political complex reacts to figures like Trump and Musk. The horror and incomprehension they inspire among elite institutions can be understood as the old liberal-rationalist order recoiling from its own obsolescence, unable to accept that the world is moving on.

The next part of this series is coming soon. Edit: The War for Attachment: The End of Rational Delusion and the Return of Organic Order

For the purposes of this essay, liberal rationalism refers to the dominant mode of discourse in the contemporary West: one that prioritizes individual autonomy and rights and the primacy of reason in addressing social and moral issues. Broadly speaking, this mode of discourse is a product of the Enlightenment, and emphasizes abstract, universal principles – such as justice, equality, and freedom – while arguing that decisions and actions should be guided by rational, objective reasoning rather than emotion, tradition, or inherited authority. This mode of discourse relies on language that is formal, logical, and detached from particular cultural or affective (emotional) contexts. In practice, it often promotes secularism, individualism, and market-based solutions while distancing itself from emergent, pre-rational forms of social cohesion and collective identity. Crucially, it presents itself not as one worldview among others, but as synonymous with reason itself. While this standard is not always attained in public discourse (eg, with asymmetric treatment of different ethnic groups), it is always treated as a paradigm – most of all, ironically, by mainstream conservatives, who typically complain that woke progressives are not ‘living up’ to the values of liberalism.

To cut a long story short, this is because liberal rationalism, at its core, is hostile to pre-rational forms of affective attachment, and thereby attacks the very structure of human experience. It assumes that discourse must always be justified in terms of abstract reason, rather than something else (eg, feeling or affect). But this is not a universal or self-evident truth: it is a contingent ideological construct. Affective attachment, by contrast, does not operate through abstract rationalization, but is embedded in behaviour, language, instinct, and tradition. As Ludwig Wittgenstein (discussed elsewhere in this essay) observed, each of us knows this intuitively, even if philosophy misleads us.

I recognize that some readers may find the ensuing treatment of a sacred subject profane or irreverent. However, my aim here is not to diminish the spiritual or theological significance of Christ’s words, but rather to explore the discursive power of His mode of communication. This is an analysis of rhetoric, not an attempt to simplify or trivialize Christ’s teachings.

> liberal rationalism, at its core, is hostile to pre-rational forms of affective attachment, and thereby attacks the very structure of human experience

The interesting thing is that there's a very rational argument supporting the existence of such *affective attachment*: see Antonio R. Damasio's *Descates' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain*. It gives a fascinating exposition on why pure reason is insufficient for action: any plan which lacks emotional colouration will not be implemented due to sheer lack of motivation.